Applications

A comprehensive list of applications using Circuitscape has been compiled in this document.

Circuitscape has rapidly become the most widely used connectivity analysis package in the world. It is used by numerous state, federal, and local agencies in the USA, and by government ministries and NGOs for conservation planning on six continents. It routinely appears in journals like PNAS, Nature Genetics, Ecology, Ecological Applications, Ecology Letters, Landscape Ecology, Evolution, Heredity, Bioscience, Molecular Ecology, Conservation Biology, and many others. In 2015 alone, Circuitscape appeared in 80 peer-reviewed journal articles—a 40% increase from 2014—plus dozens of dissertations, reports, and book chapters.

A Sampling of Circuitscape Applications from Around the World

Wildlife corridor design

Within the Nature Conservancy, connectivity analyses using Circuitscape are being used in planning exercises affecting tens of millions of dollars for land acquisition, restoration, and management. Other NGOs, whether small ones like the Snow Leopard Conservancy or large ones like the Wildlife Conservation Society, are using Circuitscape to set conservation priorities. Here are some recent examples of research in this area.

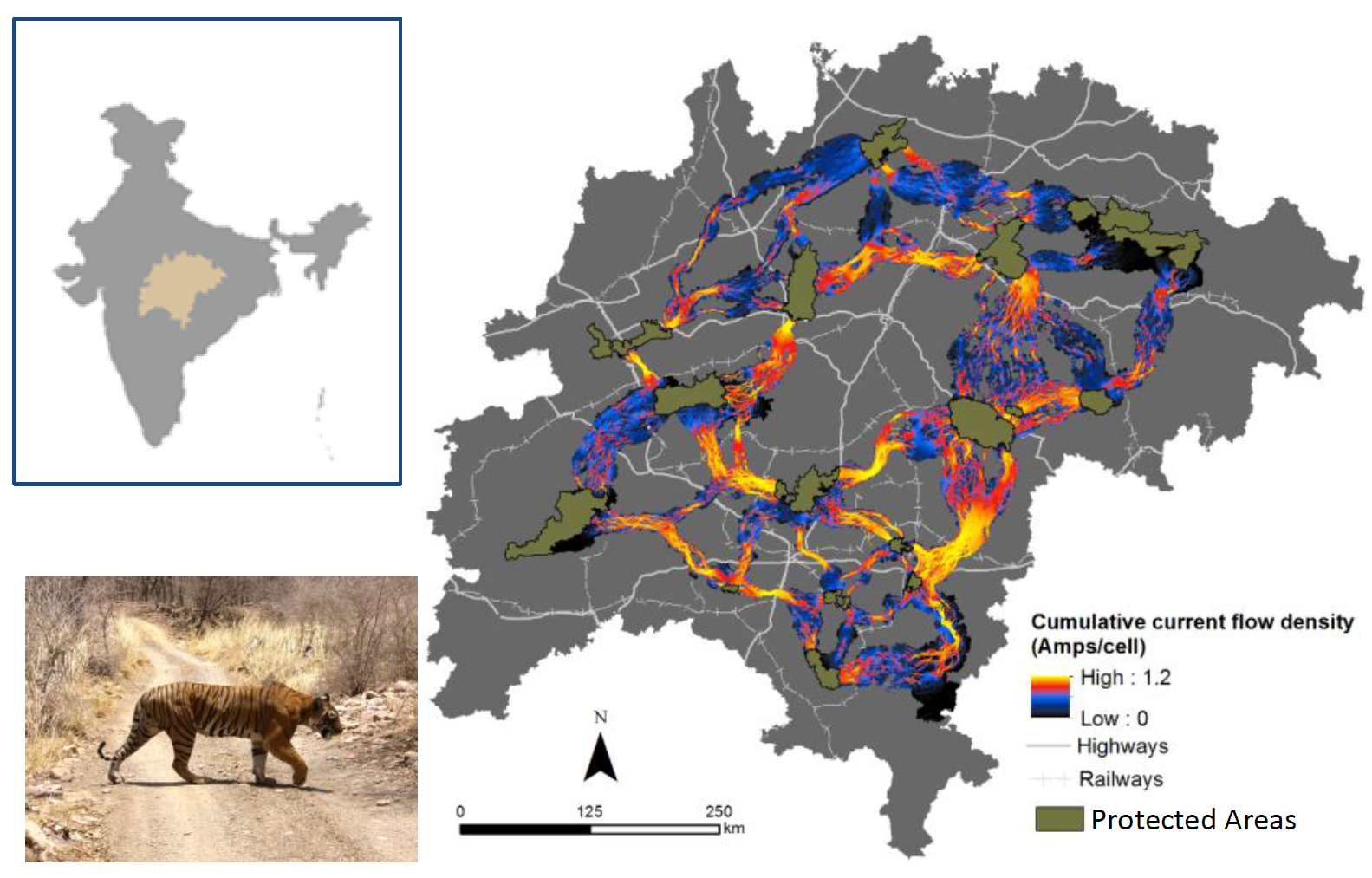

Multispecies connectivity planning in Borneo (Brodie et al. 2015).Connectivity for pumas in Arizona and New Mexico (Dickson et al. 2013).Large landscape planning across Ontario, Canada (Bowman and Cordes 2015).Connectivity prioritization for gibbons (Vasudev and Fletcher 2015).Corridors for tigers in India (Joshi et al. 2013, Dutta et al. 2015).Connectivity for Amur leopards in China (Jiang et al. 2015).Trans-boundary conservation of Persian leopards in Iran, Turkey, Armenia, and Azerbaijan (Farhadiniaa et al. 2015).Multi-scale connectivity planning in Australia (Lechner et al. 2015).Wall-to-wall’ methods that don’t require core areas to connect (Anderson et al. 2012, 2014, Pelletier et al. 2014).

Dutta et al. (2015) combined Circuitscape with least-cost corridor methods to map pinch points within corridors connecting protected areas for tigers in central India. Areas with high current flow are most important for tiger movements and keeping the network connected.

Landscape genetics

Landscape genetics is the study of how landscape pattern (the distribution of suitable habitat, barriers, etc.) affects gene flow and genetic differentiation among plant and animal populations. Circuitscape is widely used in this field, and has been combined with genetic data to show

the resilience of montane rainforest lizards to past climate change in the Australian tropics (Bell et al. 2010);

how oil palm plantations isolate squirrel monkeys in Costa Rica, and where corridors of native trees could reconnect populations (Blair et al. 2012);

how the pattern of climatically stable habitat structures genetics of canyon live oaks (Ortego et al. 2014);

how genetics and connectivity models can be combined to design Indian tiger corridors (Yumnam et al. 2014);

how urban trees facilitate animal gene flow (Munshi-South 2012);

how climate change and montane refugia have structured salamander populations in southern California (Devitt et al. 2013);

the effects of landscape change on movement among prairie dog colonies (Sackett et al. 2012); and

how landscape features influence genetic connectivity for dozens of species, from songbirds in British Columbia (Adams et al. 2016) to army ants in Panama (Pérez-Espona et al. 2012).

Movement ecology

Circuit theory can also be used to predict movements of animals and how these affect overall population connectivity. As with landscape genetics, this application is tightly tied to conservation planning. Examples include

movements of African wild dogs and cheetahs in South Africa (Jackson et al. 2016);

wolverine dispersal in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (McClure et al. 2016);

how periodic flooding affects connectivity for amphibians in Australia (Bishop-Taylor et al. 2015);

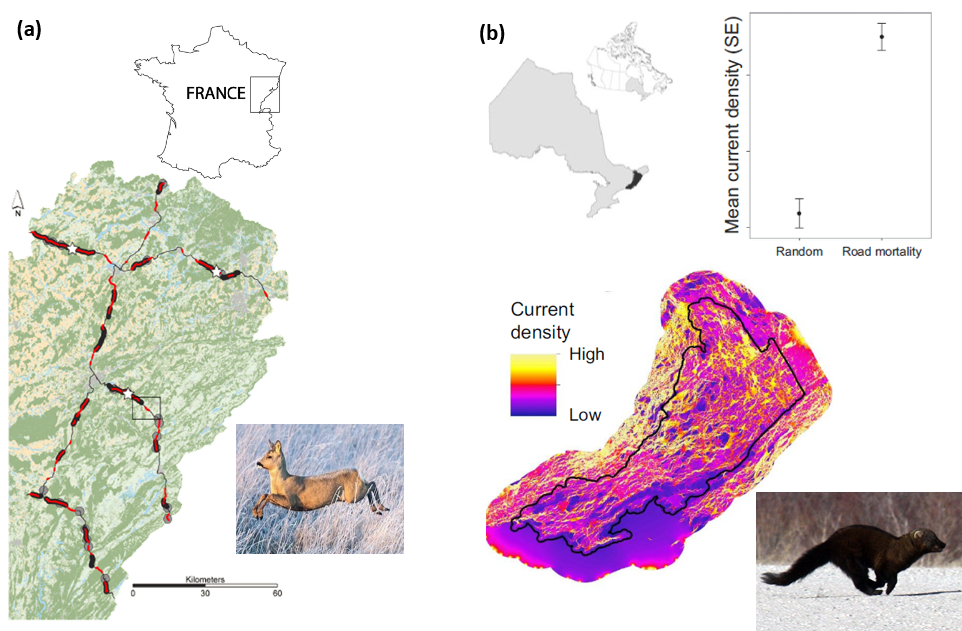

predicting where mitigating road impacts on connectivity would reduce wildlife mortality in France (Girardet et al. 2015) and Canada (Koen et al. 2014);

movement and gap crossing behavior of forest interior songbirds (St. Louis et al. 2014); and

how local abundance and dispersal scale up to affect metapopulation persistence and community stability (Brodie et al. 2016).

Circuit theory is being used to mitigate road impacts on wildlife and improve driver safety in at least six countries. (a) Circuit theory (implemented using Graphab) outperformed other connectivity models for predicting vehicle collisions with roe deer in France (Girardet et al. 2015). (b) A wall-to-wall connectivity map created using Circuitscape was highly correlated with road mortality for amphibians and reptiles and habitat use by fishers in eastern Ontario, Canada (from Koen et al. 2014). Similar methods are now being used across Ontario and in many other parts of Canada.

Connectivity for climate change

Predicting important areas for range shifts under climate change is an exciting new application of Circuitscape. One of the most important ways species have responded to past climatic changes has been to shift their ranges to track suitable climates. Rapid warming projected for the next century means many species and populations will need to move even faster than in the past or face extinction. Many species are already moving in response to rapid warming, but they are encountering barriers—like roads, agricultural areas, and cities—that weren’t present in the past. In order for species to maintain population connectivity and the ability to adapt to climate change, we need to identify and conserve important movement routes. Here are some ways Circuitscape can be used to address this need:

Hodgson et al. (2012) showed how circuit theory can be used to design landscapes that promote rapid range shifts.

Lawler et al. (2013) used Circuitscape to project movements of nearly 3000 species in response to climate change across the Western Hemisphere. See an animation of their results here.

Razgour (2015) combined species distributions, climate projections, genetic data, and Circuitscape to predict range shift pathways for bats in Iberia.

New methods connecting natural lands to those that have similar projected future climates (Littlefield et al. in review) and connecting across climate gradients (McRae et al. in 2016) are in active development.

Projected climate-driven range shifts of 2903 species in response to climate change using Circuitscape. Arrows represent the direction of modelled movements from unsuitable climates to suitable climates via routes that avoid human land uses. From Lawler et al. (2013). Explore the full animation of these results here.

New applications: infectious disease, fire, and agriculture

Circuitscape is breaking into new areas like epidemiology, invasive species spread, archaeology, and fire management. Examples include

how road networks drive HIV spread in Africa (Tatem et al. 2012);

spread of invasive insects, including disease-carrying mosquitos (Cowley et al. 2015, Andraca- Gómez et al. 2015, Medley et al. 2014);

understanding why species reintroductions succeed or fail (Ziółkowska et al. 2016);

spread of a disease that is threatening rice production in Africa (Trovão et al. 2015);

spread of rabies (Barton et al. 2010, Rioux Paquette et al. 2014);

how climate and habitat fragmentation drive Lyme disease at its range limit (Simon et al. 2014).

fuel connectivity and wildfire risk (Gray and Dickson 2015, 2016); and

strategic fuel breaks to protect sage-grouse habitat from wildfire (Welch et al. 2015).

Fire likelihood across Arizona’s lower Sonoran Desert, using Circuitscape to model fuel connectivity. Areas with high predicted fire risk corresponded with burned area data showing where wildfires occurred from 2000 to 2012 (Gray and Dickson 2015). This method has been extended to evaluate fuel treatments where invasive cheatgrass is increasing fire (Gray and Dickson 2016).

Welch et al. (2015) used a similar analysis to identify strategic areas for fuel breaks to protect greater sage-grouse habitat.

How Circuitscape Complements other Models

Circuitscape isn’t the right modeling method for every connectivity application, but it is strongly complementary to others, and often works well in conjunction with other methods. For example, McClure et al. (2016) compared least-cost paths and Circuitscape for predicting elk and wolverine movements using GPS-collared animals. They found that Circuitscape outperformed least-cost paths for predicting wolverine dispersal, but slightly underperformed them for elk. This makes sense, because circuit models reflect random exploration of the landscape, and dispersing juvenile wolverines are making exploratory movements since they do not have perfect knowledge. Elk, on the other hand, are following routes established over generations, and have much better knowledge of the best pathways.

Hybrid approaches

New hybrid methods are taking advantage of both circuit and least-cost methods. In their tiger study, Dutta et al. (2015) combined least-cost corridors and Circuitscape to map the most important and vulnerable connectivity areas connecting tiger reserves. And in their work on invasive mosquitoes, Medley et al. (2014) found that circuit and least-cost-based analyses complemented each other, with differing strengths at different movement scales and in different contexts. Using the two models in concert gave the most insight into mosquito movement and spread. Other papers that combine methods, taking advantage of different strengths for different processes and scales, include Rayfield et al. (2015), Lechner et al. (2015), Fagan et al. (2016), and Ziółkowska et al. (2016).

References

Adams R V, Burg TM. 2014. Influence of ecological and geological features on rangewide patterns of genetic structure in a widespread passerine. Heredity 114:143–154.

Anderson MG, Barnett A, Clark M, Ferree C, Olivero Sheldon A, Prince J. 2014. Resilient Sites for Terrestrial Conservation in the Southeast Region. The Nature Conservancy, Boston, MA. 127 pp.

Anderson MG, Clark M, Sheldon AO. 2012. Resilient Sites for Terrestrial Conservation in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic Region. The Nature Conservancy, Eastern Conservation Science. The Nature Conservancy, Boston, MA.

Andraca-Gómez G, Ordano M, Boege K, Dominguez CA, Piñero D, Pérez-Ishiwara R, Pérez-Camacho J, Cañizares M, Fornoni J. 2015. A potential invasion route of Cactoblastis cactorum within the Caribbean region matches historical hurricane trajectories. Biological Invasions 17:1397–1406.

Barton HD, Gregory AJ, Davis R, Hanlon CA, Wisely SM. 2010. Contrasting landscape epidemiology of two sympatric rabies virus strains. Molecular Ecology 19:2725–2738.

Bell RC, Parra JL, Tonione M, Hoskin CJ, MacKenzie JB, Williams SE, Moritz C. 2010. Patterns of persistence and isolation indicate resilience to climate change in montane rainforest lizards. Molecular Ecology 19:2531–2544.

Bishop-Taylor R, Tulbure MG, Broich M. 2015. Surface water network structure, landscape resistance to movement and flooding vital for maintaining ecological connectivity across Australia’s largest river basin. Landscape Ecology 30:2045–2065.

Blair ME, Melnick DJ. 2012. Scale-dependent effects of a heterogeneous landscape on genetic differentiation in the Central American squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedii). PLoS ONE 7.

Bowman J, Cordes C. 2015. Landscape connectivity in the Great Lakes Basin.

Brodie JF, Giordano AJ, Dickson B, Hebblewhite M, Bernard H, Mohd-Azlan J, Anderson J, Ambu L. 2015. Evaluating multispecies landscape connectivity in a threatened tropical mammal community. Conservation Biology 29:122–132.

Brodie JF, Mohd‐Azlan J, Schnell JK. 2016. How individual links affect network stability in a large‐scale, heterogeneous metacommunity. Ecology.

Cowley DJ, Johnson O, Pocock MJO. 2015. Using electric network theory to model the spread of oak processionary moth, Thaumetopoea processionea, in urban woodland patches. Landscape Ecology 30:905–918.

Devitt TJ, Devitt SEC, Hollingsworth BD, McGuire JA, Moritz C. 2013. Montane refugia predict population genetic structure in the Large-blotched Ensatina salamander. Molecular ecology 22:1650–65.

Dickson BG, Roemer GW, McRae BH, Rundall JM. 2013. Models of regional habitat quality and connectivity for pumas (Puma concolor) in the Southwestern United States. PLoS ONE 8.

Dutta T, Sharma S, McRae B, Roy P, DeFries R. 2015. Connecting the dots: mapping habitat connectivity for tigers in central India. Regional Environmental Conservation:1–15.

Fagan ME, DeFries RS, Sesnie SE, Arroyo JP, Chazdon RL. 2016. Targeted reforestation could reverse declines in connectivity for understory birds in a tropical habitat corridor. Ecological Applications.

Farhadinia MS, Ahmadi M, Sharbafi E, Khosravi S, Alinezhad H, Macdonald DW. 2015. Leveraging trans-boundary conservation partnerships: Persistence of Persian leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor) in the Iranian Caucasus. Biological Conservation 191:770–778.

Girardet X, Conruyt-Rogeon G, Foltête JC. 2015. Does regional landscape connectivity influence the location of roe deer roadkill hotspots? European Journal of Wildlife Research 61:731–742.

Gray ME, Dickson BG. 2015. A new model of landscape-scale fire connectivity applied to resource and fire management in the Sonoran Desert, USA. Ecological Applications 25:1099–1113.

Gray ME, Dickson BG. 2016. Applying fire connectivity and centrality measures to mitigate the cheatgrass-fire cycle in the arid West, USA. Landscape Ecology.

Heller NE, Zavaleta ES. 2009. Biodiversity management in the face of climate change: A review of 22 years of recommendations. Biological Conservation 142:14–32.

Hodgson JA, Thomas CD, Dytham C, Travis JMJ, Cornell SJ. 2012. The Speed of Range Shifts in Fragmented Landscapes. PLoS ONE 7.

Jackson CR, Marnewick K, Lindsey PA, Røskaft E, Robertson MP. 2016. Evaluating habitat connectivity methodologies: a case study with endangered African wild dogs in South Africa. Landscape Ecology:1–15.

Jiang G et al. 2015. New hope for the survival of the Amur leopard in China. Scientific Reports 5:15475.

Joshi A, Vaidyanathan S, Mondo S, Edgaonkar A, Ramakrishnan U. 2013. Connectivity of tiger (Panthera tigris) populations in the human-influenced forest mosaic of central India. PLoS ONE 8.

Koen EL, Bowman J, Sadowski C, Walpole AA. 2014. Landscape connectivity for wildlife: Development and validation of multispecies linkage maps. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 5:626–633.

Lawler JJ, Ruesch AS, Olden JD, McRae BH. 2013. Projected climate-driven faunal movement routes. Ecology Letters 16:1014–1022.

Lechner AM, Doerr V, Harris RMB, Doerr E, Lefroy EC. 2015. A framework for incorporating fine-scale dispersal behaviour into biodiversity conservation planning. Landscape and Urban Planning 141:11–23.

Littlefield CE, McRae, B.H. Michalak J, Lawler JJ, Carroll C. (n.d.). Missed connections: Tracking climates through time and space to predict connectivity under climate change. Conservation Biology.

McClure M, Hansen A, Inman R. 2016. Connecting models to movements: testing connectivity model predictions against empirical migration and dispersal data. Landscape Ecology.

McRae BH. 2006. Isolation by resistance. Evolution 60:1551–1561.

McRae BH, Dickson BG, Keitt TH, Shah VB. 2008. Using circuit theory to model connectivity in ecology, evolution, and conservation. Ecology 89:2712–2724.

McRae BH, Popper K, Jones A, Schindel M, Buttrick S, Hall K, Unnasch RS, Platt JT. 2016. Conserving Nature’s Stage: Mapping Omnidirectional Connectivity for Resilient Terrestrial Landscapes in the Pacific Northwest. The Nature Conservancy, Portland Oregon. 47 pp. Available online at: https://nature.org/resilienceNW.

Medley KA, Jenkins DG, Hoffman EA. 2015. Human-aided and natural dispersal drive gene flow across the range of an invasive mosquito. Molecular Ecology 24:284–295.

Munshi-South J. 2012. Urban landscape genetics: Canopy cover predicts gene flow between white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus) populations in New York City. Molecular Ecology 21:1360–1378.

Ortego J, Gugger PF, Sork VL. 2015. Climatically stable landscapes predict patterns of genetic structure and admixture in the Californian canyon live oak. Journal of Biogeography 42:328–338.

Pelletier D, Clark M, Anderson MG, Rayfield B, Wulder MA, Cardille JA. 2014. Applying circuit theory for corridor expansion and management at regional scales: Tiling, pinch points, and omnidirectional connectivity. PLoS ONE 9.

Pérez-Espona S, McLeod JE, Franks NR. 2012. Landscape genetics of a top neotropical predator. Molecular Ecology 21:5969–5985.

Rayfield B, Pelletier D, Dumitru M, Cardille JA, Gonzalez A. 2015. Multipurpose habitat networks for short-range and long-range connectivity: A new method combining graph and circuit connectivity. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 7:222–231.

Razgour O. 2015. Beyond species distribution modeling: A landscape genetics approach to investigating range shifts under future climate change. Ecological Informatics 30:250–256.

Rioux Paquette S, Talbot B, Garant D, Mainguy J, Pelletier F. 2014. Modelling the dispersal of the two main hosts of the raccoon rabies variant in heterogeneous environments with landscape genetics. Evolutionary Applications 7:734–749.

Roever CL, van Aarde RJ, Leggett K. 2013. Functional connectivity within conservation networks: Delineating corridors for African elephants. Biological Conservation 157:128–135.

Sackett LC, Cross TB, Jones RT, Johnson WC, Ballare K, Ray C, Collinge SK, Martin AP. 2012. Connectivity of prairie dog colonies in an altered landscape: Inferences from analysis of microsatellite DNA variation. Conservation Genetics 13:407–418.

Simon JA et al. 2014. Climate change and habitat fragmentation drive the occurrence of Borrelia burgdorferi, the agent of Lyme disease, at the northeastern limit of its distribution. Evolutionary Applications 7:750–764.

St-Louis V, Forester JD, Pelletier D, Bélisle M, Desrochers A, Rayfield B, Wulder MA, Cardille JA. 2014. Circuit theory emphasizes the importance of edge-crossing decisions in dispersal-scale movements of a forest passerine. Landscape Ecology 29:831–841.

Tatem AJ, Hemelaar J, Gray RR, Salemi M. 2012. Spatial accessibility and the spread of HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants. AIDS 26:2351–2360.

Trovão NS, Baele G, Vrancken B, Bielejec F, Suchard MA, Fargette D, Lemey P. 2015. Host ecology determines the dispersal patterns of a plant virus. Virus Evolution 1:vev016. 1.

Vasudev D, Fletcher RJ. 2015. Incorporating movement behavior into conservation prioritization in fragmented landscapes: An example of western hoolock gibbons in Garo Hills, India. Biological Conservation 181:124–132.

Welch N, Provencher L, Unnasch RS, Anderson T, McRae B. 2015. Designing regional fuel breaks to protect large remnant tracts of Greater Sage‐Grouse habitat in parts of Idaho, Nevada, Oregon, and Utah. Final Report to the Western Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies, Contract Number SG-C-13-02. The Nature Conservancy, Reno, NV.

Yumnam B, Jhala Y V., Qureshi Q, Maldonado JE, Gopal R, Saini S, Srinivas Y, Fleischer RC. 2014. Prioritizing tiger conservation through landscape genetics and habitat linkages. PLoS ONE 9.

Ziółkowska E, Perzanowski K, Bleyhl B, Ostapowicz K, Kuemmerle T. 2016. Understanding unexpected reintroduction outcomes: Why aren’t European bison colonizing suitable habitat in the Carpathians? Biological Conservation 195:106–117.